29th July 2020

How to be a saint in York

Alan Atkinson wrote a guest blog post for us from Australia:

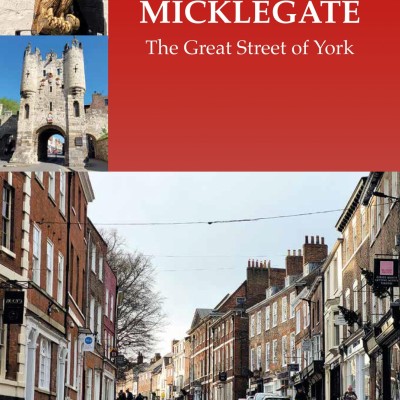

There is a wonderful book waiting to be written about the community of women who lived at Micklegate Bar during the 1700's - and since that time. The community, the Convent of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin, still flourishes at the same place in Blossom Street.

My three-times-great-grandfather’s sister lived there, from girlhood until her death in 1779. I learnt about her first from an enormous family tree brought to Australia in 1854-55, when my forebears came to this country. There’s the tantalising line: “ELIZABETH, born 1727; entered York Convent June 27, 1737; took the veil (under name “Sister Ursula”) 1743, and died there, April, 1779, aged 52”.

When I wrote to the convent in 2007 I was very kindly helped by the then archivist, Sister Christina Kenworthy-Browne CJ (herself a historian). The archives have detailed records of nearly all the women who lived there - almost as if the convent itself, in its Christian charity, knew what future family historians would really like.

The Church used the lives of the saints, and even the more-or-less saintly, as a teaching tool. Happily, my own forebear, Elizabeth Atkinson, was thought of by her community as a minor saint. No-one else knew she existed.

The nuns were gentlewomen and they knew it, but Elizabeth’s brother and sister-in-law had fallen on hard times and she got the convent to employ her sister-in-law to come in with her daughters to do their washing. She almost boasted about the connection. So, the record says, “when she might have said, as others of the community did, “The washerwoman is come, or wants so & so”, she invariably said, “my sister or my niece wants so & so”. Imagine! In that place, it was a striking example of self-humiliation, treasured and written up, so as to make “a deep impression on the young Ladies” - the new girls coming in.

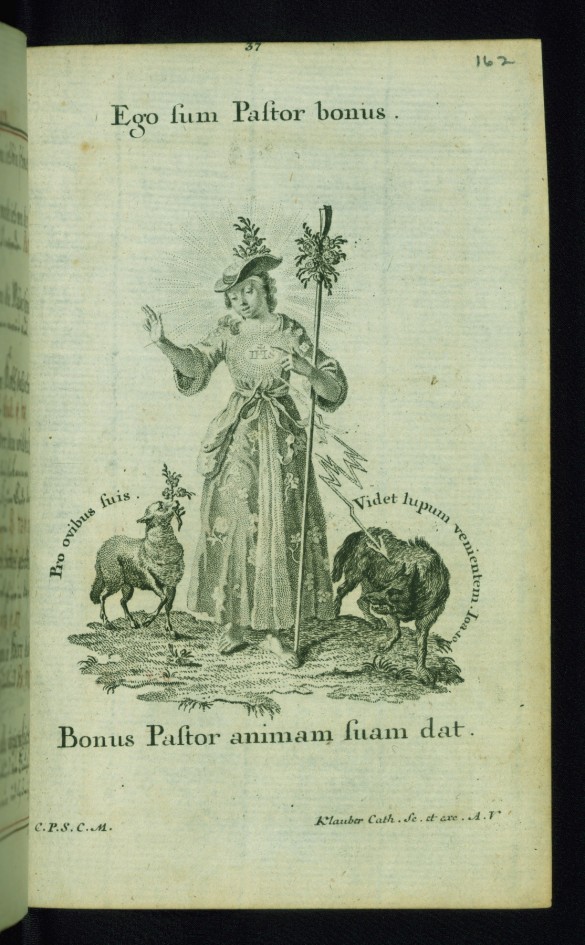

But what really proved Elizabeth’s saintliness was her being addressed, face-to-face, by her Saviour. As she got older she suffered from mental depression and general debility, and she begged for relief before an image of the Good Shepherd. At length the image answered, “I will help you soon”, but when nothing happened she tried mild reprimand. “The ‘soons’ of God”, she told the Good Shepherd, “are very long”. More waiting and then it was, “Lord, no one will help me”, until at last he did.