Children and young people in York workhouse, 1879-1887

This is one of a series of posts about young people. Others examine the origins of boarding-out (fostering) from the workhouse and apprenticeship indentures. This post looks at aspects of gender relations, and the lives of girls on leaving the workhouse.

Children were admitted to the workhouse on Huntington Road for a variety of reasons. Some were orphaned or deserted, others left by parents, a decision often prompted by fluctuating household income. Admission was sometimes due to too many children at home, with parents unable to maintain them all. Children might be left in the workhouse for only a few days or weeks till circumstances at home improved. Some – the 'outs and ins' – had two or more stays in the workhouse. However, the proportion of children in York workhouse declined from 40% of inmates to 20% between 1860 and 1900.

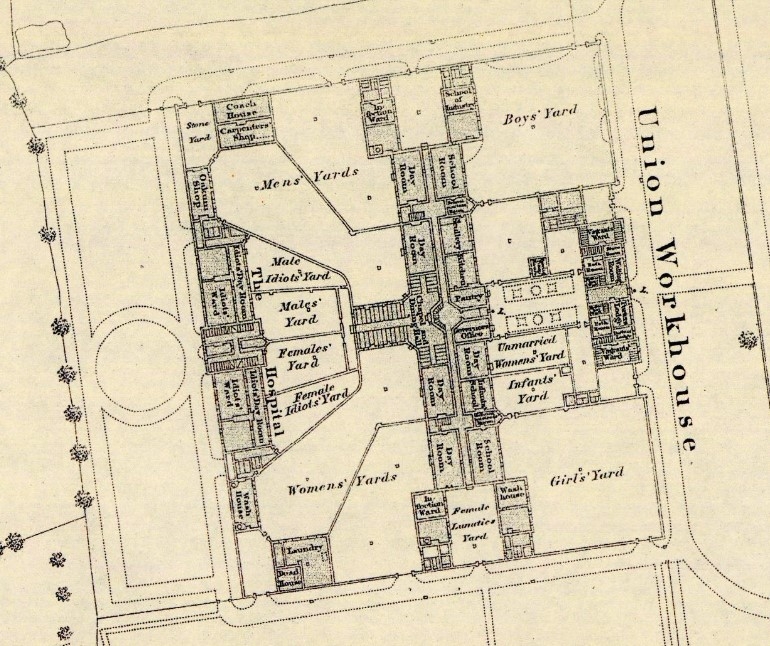

Plan of York Union Workhouse,1852 (Courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries)

This plan illustrates how segregation operated. Parents were separated from children, men from women, and girls from boys.

York workhouse held 101 boys and 107 girls under 16 in 1881. The table below notes these children, plus other family members, and the circumstances (where known) that led to their admission.

Click on link to download lists of boys and girls aged 0 to 15 in York workhouse in 1881 and summary totals of all inmates (source:1881 census).

In a pilot boarding-out (fostering) scheme in 1881-82, twenty children aged between two and eight were fostered from the workhouse. Of these 17 were girls, and three boys. Girls were thus preferred by foster parents, whilst the Board of Guardians perhaps feared workhouse 'moral contagion' of particular danger to girls. Moreover, there was financial pressure to discharge girls, as overcrowding in the girls' workhouse quarters would have otherwise have required funds to construct an extension. Guardians' concern for ratepayers' interests demanded financial prudence.

Boys were often more likely than girls to be placed in the workhouse, as they were viewed by many parents as better able to survive on their own. Girls were more valued at home, providing childcare for younger siblings, or acting as surrogate mother, if their mother had died or was ill – and seen as more useful in helping with domestic duties. There may also have been a perception that boys were more difficult to raise, especially as teenagers, and more likely to disrupt the home.

Between 1879 and 1887 there were 74 boy and 29 girl apprentice and domestic service bindings. 20 of the girls were placed in York, the remainder in North, East and West Ridings, and Durham. Domestic service was the largest occupation of women in 19th century Britain, with one in three women in Victorian England a domestic servant at some stage in her life. However, inconsistencies in calculating the numbers of servants between censuses creates difficulty in interpreting occupational census tables. e.g. the 1891 census includes all women 'helping at home' as domestic servants.

Historically, demand for domestic servants had been high among York's propertied classes, with one-servant families also common. However, by 1881 the York Association for the Care of Young Girls was reporting its Young Women's Institute at 16 Micklegate had received many applications for servants which it had been unable to supply. The demanding nature of domestic service was prompting some mothers to encourage daughters to choose alternative employment, such as factory work which offered better wages and conditions. This preference was expressed by some girls too.

Historically, demand for domestic servants had been high among York's propertied classes, with one-servant families also common. However, by 1881 the York Association for the Care of Young Girls was reporting its Young Women's Institute at 16 Micklegate had received many applications for servants which it had been unable to supply. The demanding nature of domestic service was prompting some mothers to encourage daughters to choose alternative employment, such as factory work which offered better wages and conditions. This preference was expressed by some girls too.

A maid bringing medicine and soup to her master who has a cold. Lithograph, 1857, after W.H. Simmons after J. Collinson. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Case study

Sarah J. Pratt was born in 1866 to Henry and Naomi Pratt in Stillingfleet. Henry (63) was the village blacksmith, his wife only 34, according to the 1871 census. Sarah was four, with a brother Charles (six).

Henry is recorded on the 1881 census as a widower (78) living with son Charles (16). Sarah (14) was now a York workhouse inmate, with her siblings Eliza (12), and twins Thomas and John (9). It appears the death of her mother, and the inability of her aged father to cope, propelled the children into the workhouse.

Sarah was discharged from the workhouse on 6 October 1881, to work as a domestic servant for John Lane (26), a coal dealer at 17 Eldon Street, York. Lane lived with his wife and two very young children, along with his sister-in-law (30) and a male boarder (62), described on the census form as a 'Chelsea pensioner'.

By 1891 Sarah was a general domestic servant in the household of Robert Gamble, a farmer of Kelfield. She married William Riley, a chimney sweep, in 1895 and was living with him at 12 Little Shambles in 1905. Confusingly she is recorded as sister, not wife. Two sons are listed, William (17) and John H (14), and a daughter, Beatrice (1). Given Sarah was single and in service on the 1891 census this suggests William might have been married before and William and John were sons of that earlier marriage.

In 1911 Sarah is noted as William’s wife, living at St John’s Place, Haver Lane, Hungate, with her sons John H (24), Harold (5) and Sydney (2). Beatrice appears to have died in 1909, aged 9. By 1939 Sarah is widowed and resident again at the workhouse at 72 Huntington Road. She appears to have died in York in 1951.

Follow this link to our notes on eight girls who left York workhouse to work in domestic service.

Further research

There is potential for further research of young women who left the workhouse.

Primary sources

Census 1881-1921

York Association for the Care of Young Girls Annual Report 1881, p. 10. Explore York Libraries & Archives, CYG/2 .

York Poor Law Union Admission & Discharge Book 1880-82, Explore York Libraries & Archives, PLU/2/1/1/1.

York Poor Law Union Board of Guardian Minute Books, 1879-87, Explore York Libraries & Archives, PLU/1/1/1/21-25.

York Poor Law Union Index to Admission & Discharge Books, 1889-1899, Explore York Libraries & Archives PLU/2/1/1/2

Secondary sources

Digby, Anne, 'The Relief of Poverty in Victorian York: Attitudes and Policies' in Feinstein, C.H. (ed.), York 1831-1981: 150 Years of Scientific Endeavour and Social Change (The Ebor Press in association with the British Association for the Advancement of Science (York Committee), 1981).

Hey, David (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Family & Local History, 2nd edition, (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Horn, P., The Rise and Fall of the Victorian Servant, (Gill & Macmillan, 1975).

Website

https://www.workhouses.org.uk/

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kate Gibson (University of Manchester), Julie-Ann Vickers (Explore York Libraries & Archives), and Catherine Oakley (Rowntree Society) for assistance.

This post is by Judith Hoyle, Elaine Bradshaw and Dick Hunter.