From stray cows to iron horses: how Francis Bean escaped poverty

Group member Elaine Bradshaw has been carrying out research into a local family, to explore the factors behind the decline and later improvement in the life prospects of young Francis Bean. This is part of 'Making Ends Meet in Nunnery Lane', our research project focusing on 19th poverty.

Francis Bean came from an old York family of small craftsmen and traders, all Freemen of the City of York. Freemen had several very important rights, many going back to the Middle Ages. [i] Most importantly, only Freemen could 'exercise a trade in the city'; and only Freemen and property owners could vote for Members of Parliament. They could also 'depasture' animals on the Strays, the remnants of the old common grazing grounds. However in 1835, the Municipal Reform Act removed many of their powers and opened up the running of the City to a wider range of people. Freeman of the City was still an honourable title [ii], and for several generations after 1835, the Beans were proud to claim it as their birthright through patrimony.

Francis’s grandfather was Thomas Bean, a currier in Jubbergate, York (a currier is a craftsman in leather, taking the tanned hides and finishing them). His wife was most probably Sarah Acomb, daughter of a farmer from Wheldrake. (Identifying the mother was quite a challenge, and I have settled on Sarah as being the most likely.[iii])

Later, Thomas diversified into cow-keeping[iv] and is mentioned in several White’s Directories of York, from 1840 onwards. There were lots of cow-keepers in York at this time, continuing into the 1850s. Because milk was such a perishable commodity, it had to be produced close to the markets, so cows were grazed in the fields and strays near the City, or kept in backyard cowsheds, even in densely populated parts of the City. (We have found two in the small area around Swann Street that we have been researching.) Although the Freemen lost most of their powers in 1835, they retained their grazing rights, so Thomas was allowed to graze two cows, most likely on Micklegate Stray, given that he lived in Micklegate Ward. [v] (The other Strays were Bootham, Monk, and Walmgate). This may not have been enough to run a business with, but he could have bought the allocation, or 'gate' from another Freeman. I do not know whether Thomas’s main business was in animal hides or milk. He was a currier when he applied to be a Freeman of York and on the 1841 and 1851 censuses, though his wife called herself widow of Thomas Bean, cow-keeper, on the York Cemetery records, and she took over the cow-keeping after his death.

For most of Thomas’s life – certainly from 1846[vi] - he lived in South Prospect Street. The house is long gone, but it was on the Tadcaster Road, backing on to Hob Moor and facing the pinfold (pound) on the Knavesmire, so right in the middle of Micklegate Stray.

Whether he earned his money as a currier or a cow-keeper, Thomas was a prosperous and influential member of the community. When he died of 'natural decay' in 1853, he left £100.[vii] He was able to buy a family-sized plot in York Cemetery, furnished with a headstone which still exists,[viii] where his widow Sarah, and most of his children, were also buried in their turn.

Thomas was a Freeman before 1835, when the Freemen still had powers and provided a pool of candidates for the officers of the City. Thomas exercised his civic duties for over 30 years as Assistant Overseer for the Parish of St Mary Bishophill Junior, so he collected the Poor Rates and redistributed it to the needy. His obituary charitably notes that he was respected by all who knew him.[ix] However, in March 1850 a case for non-payment of poor rates by another cow-keeper had to be adjourned because of Thomas’s unreasonable behaviour - he banged the table on three or four occasions and demanded immediate payment. It was noted that “Thomas Bean was in liquor,”[x] though this did not prevent him from being re-elected the following year. Thomas was obviously capable of being quite cantankerous.

Thomas and Sarah’s oldest son, and Francis’s father, was Robert, and some of the gaps and discrepancies in the records of the Bean family could hint that Robert may also have found his father difficult. As a young man, Robert spent some time away from York in Wheldrake, where his mother came from, working as a servant. [xi] When he married, he did not provide details of his father’s name or occupation, which is extremely unusual.[xii]

Robert returned to York aged 21 and became a Freeman of the City, for which he qualified by patrimony, since his father had been a Freeman at the time of his birth. When he was admitted in 1832 he was still working as a servant in Wheldrake, but later he became a cow-keeper like his father. Robert was a cow-keeper when he married Mary Eccles in 1837, when his first children were born, and when he is noted in the 1841 Census. He was then living in Albion Street in the parish of All Saints, North Street.

Francis’s early life

By the time Francis was born in 1845,[xiii] Robert had become an innkeeper at the Red Lion, 64 Micklegate. He appears in several Slater’s and White’s trade directories up until 1848, and was still living in Micklegate and working as a publican when his daughter Mary was baptised, at Holy Trinity in 1849. Then there was a downturn in the family’s fortunes. By the 1851 census they had moved to Swann Street and Robert was working as a labourer. He would be earning less, and he now had five children to support – Thomas John, Sarah, Francis, Jane and Mary. In 1852 he and Mary had one more daughter, Margaret.

By the time Francis was born in 1845,[xiii] Robert had become an innkeeper at the Red Lion, 64 Micklegate. He appears in several Slater’s and White’s trade directories up until 1848, and was still living in Micklegate and working as a publican when his daughter Mary was baptised, at Holy Trinity in 1849. Then there was a downturn in the family’s fortunes. By the 1851 census they had moved to Swann Street and Robert was working as a labourer. He would be earning less, and he now had five children to support – Thomas John, Sarah, Francis, Jane and Mary. In 1852 he and Mary had one more daughter, Margaret.

The premises of the the Red Lion at 64 Micklegate, now a lettings agency

When Francis was 10, in 1855, he was accepted into the Blue Coat School,[xiv] a clear sign that the family were struggling, as this was a charity school. It had been founded in 1705 for children of poor families, preferably those whose fathers were Freemen of York. There were other conditions of acceptance to the Blue Coat School. Your parents had to be married, so copies of birth certificates had to be produced, and the preference was for boys who were strong and healthy.

Francis provided a certified copy of his baptismal record at Holy Trinity, Micklegate, signed by the minister. Curiously, it gives his mother’s name as Elizabeth, although Mary was certainly the mother of all the other children, both older and younger. The Blue Coat School did not ask awkward questions, but when the certificate was reused in 1867 to support Francis’ application for Freeman of the City, an explanation was required. The application therefore includes a note signed by Mary – she could only manage a cross – to the effect that she was Francis’s mother and Elizabeth had been written by mistake.

The education provided by the Blue Coat School was practical rather than intellectual. The boys all worked for their keep, and when they finished school they were apprenticed or sent to sea.[xv] Parents’ educational expectations of the school were not high, but they appreciated its feeding and clothing of their sons. It was viewed it as 'an institution for maintenance' or 'a relief for families', rather than a way for their sons to get a good education.

Robert’s health deteriorated and by 1858 his name appears in the Outdoor Relief books. From 7 April to 29 September 1858 he received three shillings weekly in cash and one shilling and six pence in kind from the parish of Holy Trinity, Micklegate. He continued to decline, and at the beginning of December 1859 he received his last three shillings and one pound of flour. This time his occupation is given as innkeeper, and he is described as not ordinarily able-bodied, something of an under-statement, as under Observations someone very shortly afterwards pencilled in: Dead.

Robert Bean died on 10 December 1859, so Francis had to grow up quickly. The 14 year old boy was present at the death, and he was the one who registered it. Robert died of exhaustion with abscesses of the hips and thigh from disease of the bones. It was an awful way to die, and must have been harrowing to watch.

One immediate worry was spared the family – his burial plot. When Robert’s father Thomas died, his wife Sarah purchased a large plot in York Cemetery, where Thomas and two of his daughters already lay. Robert joined them there and, although he is not named on the gravestone, his details can be found in York Cemetery Register.[xvi]

How will the Beans survive?

This table shows the remaining family and the money they were earning, taken from Application & Report Books from 1859-1860.

Name |

Age |

Occupation |

Weekly earnings |

Mary Bean |

41 |

Widow |

- |

Thomas John Bean |

21 |

Apprentice marble polisher |

16s ; 10s 6d |

Sarah Bean |

19 |

Servant, living in |

not known |

Francis Bean |

14 |

Apprentice joiner |

4s |

Jane Bean |

12 |

Scholar |

Ill |

Mary Bean |

10 |

Scholar |

- |

Margaret Bean |

8 |

Scholar |

- |

TOTAL |

|

|

20s |

Only the two boys were bringing in a wage. Thomas had nearly finished his apprenticeship, and two different figures are noted for his wages. They are only a week apart. Why the discrepancy? It may be that the family downplayed his wages to make a better case for themselves. Or it could be that he had finished his apprenticeship, but not yet found a job. It took him a long time to set up as a journeyman marble polisher, and when he applied to become a Freeman he was working as a porter, so not earning a lot.[xvii] Francis had only just started his apprenticeship and was getting a pittance. Jane was just about old enough to start working as a servant – very few poor girls made it to 14 before leaving school – but was ill off and on until 1862 with 'general debility'.[xviii] Her sister Mary had epilepsy, and Margaret was only eight years old. Later applications show that their mother Mary was doing her best to earn some money by working as a charwoman, and then a nurse, both very low-paid.

The rest of the family were probably not in a position to give Mary much support. Her daughter Sarah’s wages would have been small. Robert’s mother Sarah was still alive, but the £100 left by her husband were long gone. At the age of 75, she was still working as a cow-keeper alongside her daughter-in-law, and taking in a lodger to help make ends meet. [xix]

There would have been some money from the Freemen of York. Profits from the Strays were divided among Freemen or widows of freemen, and some of the richer Freemen waived their payments, to benefit the poorer members. In 1858, 500 people received 12s each. In 1859 unfortunately there were more recipients and the payment dropped to 9 shillings.[xx] No doubt this money would have been welcome but, as it was an annual payment, it would not have made much difference to their weekly budget.

Twenty shillings was not enough for a family of this size to live on. I have used figures from Alan Armstrong’s Stability and change in an English county town[xxi] to estimate they would have needed around twenty seven shillings a week just to survive, so they fell well short.

The Beans apply for relief from the York Poor Law Union

Mary Bean first applied for relief soon after her husband’s death in December 1859, on the grounds of widowhood, and was awarded six shillings per week from the Common Charges fund, with no time limit noted. This sum actually brings the family incomings very close to Armstrong’s estimate.

Mary and her family got relief until 1862 and I tracked them through the outdoor relief system using the Application & Report (A&R) books [xxii] and the Outdoor Relief (OR) Books [xxiii] (Outdoor relief consisted of handouts in money or in kind, to enable the poor to live in the community, rather than being sent to the workhouse.) People’s first contact with the system was logged in the Application & Report (A&R) books. Their details were written down – address, family members, ages, money coming into the household, reason for applying – and the decision on relief noted. They might be sent to the workhouse, given relief or 'not entertained.' If their application was successful, then the recipient’s name was transferred to the Outdoor Relief (OR) Books and their payments were entered there week by week. If they were claiming relief because of illness, a medical certificate was required to be produced at the weekly meeting of the Board of Guardians.

Mary was far from totally destitute when she first applied. She had received the very tidy sum of eleven pounds and fifteen shillings from 'the Club' soon after her husband’s death, an amount which would support the family for eight weeks. 'The Club' is frequently mentioned in the A&R Books but the sums involved are usually small weekly payments, say 4/- to 9/-. 'The Club' actually covered a great variety of organisations. Most poor people were very aware of how precarious their lives were and they tried hard according to their means to put something aside.

The 1909 Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress [xxiv] gives a good idea of the range of thrift agencies at work in York, albeit at a slightly later period than this. There were small informal 'sharing-out clubs' organised by workshops or adult schools, or even public houses. Many people made regular payments which entitled them to a weekly sum when incapacitated.[xxv] Others could pay small and perhaps less regular amounts into the Penny Savings Bank.

There were also friendly societies. Some were tiny, but the best of them had many members and sound financial reserves. For example, York had seven branches of the Ancient Order of Foresters, which paid out £760 in sick pay in 1893, and also £323 for 38 funerals, which averages out at £8 per funeral.

I think Mary’s lump sum was intended for her husband’s funeral – either from a friendly society or a burial club. In Victorian times, it was very important for a family’s sense of worth to bury their members decently. I found two other lump sums in our database and both belonged to widows, one definitely in similar circumstances to Mary, being recently bereaved.[xxvi] So it seems that the Poor Law Union did not count money earmarked for funerals as part of the family’s resources.

Following the Bean family through the Poor Law books

Tracking the Beans’ tortuous journey through the (A&R) and (OR) Books raised lots of other questions. At one point, I was quite convinced the Beans were gaming the system. However, most of the apparent discrepancies turned out to be totally above board. Because of the complications, I will give a very brief explanation here. If you want to know the full details, please follow this link.

1 |

Why was Mary given relief when she had eleven pounds and fifteen shillings in hand? |

The lump sum was most likely for her husband’s burial |

2 |

Why did they receive money from three different parishes, none of which was Robert’s parish of settlement |

People were now being relieved in their parish of residence rather than the parish in which they were born. If their needs looked like being temporary, they were paid out of a common fund instead |

3 |

Was the system too complicated, so open to mistakes? |

No. The rules were being applied consistently, and by the same clerk, Henry Brearey |

4 |

Did Under 16 mean up to your sixteenth birthday or sixteen and under? |

Both definitions seem to have been applied to Francis |

5 |

Why was he relieved separately from the rest of the family as an Orphan under 16 without parents? |

Not sure |

6 |

Was someone in the PLU sympathetic to the Bean family? |

Possibly |

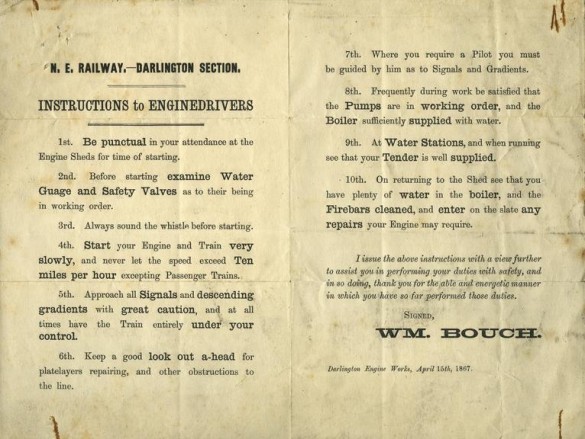

The railways came to York in the 1830s. In 1854 the North Eastern Railway was authorized, and by 1861 it was a major employer in the city. Swann Street, Dale Street and Dove Street were a conveniently short walk from York Station and 28% of the workforce in this area were railway employees in some capacity. see

The railways came to York in the 1830s. In 1854 the North Eastern Railway was authorized, and by 1861 it was a major employer in the city. Swann Street, Dale Street and Dove Street were a conveniently short walk from York Station and 28% of the workforce in this area were railway employees in some capacity. see