View navigation

Hudda Morgan has been researching one of our local families which played a key role in persuading young men to sign up for combat during the First World War:

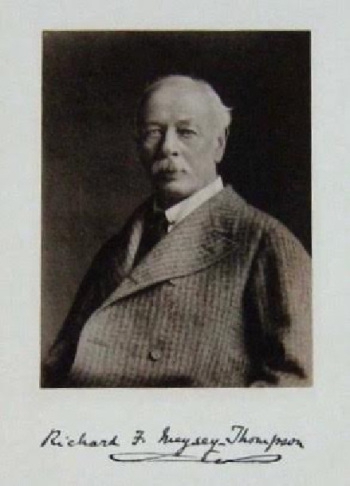

Hudda Morgan has been researching one of our local families which played a key role in persuading young men to sign up for combat during the First World War:Richard Frederick Meysey-Thompson, of Nunthorpe Court (now part of Millthorpe School in York), was a military man, from a military family. Having left Eton in 1865, he went straight into the Rifle Brigade, commencing active duty in August 1866. He fought in the second phase of the Ashanti conflict (modern day Ghana) during 1873 and 1874, for which he was awarded a service medal, and a clasp for action in Coomassie in the Battle of Amoaful. He retired from the Army in 1884, having suffered from repeated bouts of malarial fever, following his service in the Ashanti campaign. However in 1889, he was re-appointed Lt Col of the 4th Battalion Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Regiment), and in 1890 was given the honorary rank of Colonel.

Two months after the outbreak of war, in September 1914, Richard’s older brother, Henry Meysey Meysey-Thompson, Lord Knaresborough, travelled from Scotland, to hold a meeting in Great Ouseburn, at the family seat of Kirby Hall, in furtherance of the army’s recruitment drive. At the meeting, Lord Knaresborough said he was “absolutely convinced that it was imperatively necessary for every able bodied young man to join the Army at the present moment… The danger of invasion is very serious and the best way to avoid it is to ensure the success of our Army on the Continent by increasing its strength. It appears to me the plain duty of everyone who is able to do so, is to join at once. You might say it is all very well for me to tell you your duty, but ask what am I going to do? Well, a man in his seventieth year is too old, but my son [the Hon Claude Henry Meysey Meysey-Thompson – and Lord Knaresborough’s only son] is at war and might at this moment be under fire, for he is engaged in the force attacking the retreating Germans….My son-in-law Captain Vandeleur has rejoined his old regiment – the Guards. My other son-in-law is working with the Yeomanry at Knowsley, my nephew has joined the Rifle Brigade and all able-bodied members of my family have gone who could go (to which there was great applause). I urge all who can join, to do so, in their own interest. Those who stay will be sorry for it afterwards, and those who go will be happier all their lives, for they will have done a manly, plucky, and proper thing (more applause). It must be a fight to the finish and every man is wanted.”

Sadly, one month later Captain Vandeleur had been killed at Zandvoorde, aged 30. His body was never found. Nine months later Lord Knaresborough’s only son the Hon Claude Henry Meysey Meysey-Thompson, and Richard’s nephew had also been killed at Ypres, whilst serving with The Rifle Brigade. On 6th June 1915 he had been assisting his men in fixing sandbags on the parapet of a trench, but was struck by a German shell and wounded in three places. He died ten days later in hospital in Ballieol and was brought back to be buried in the family mausoleum in Great Ouseburn on 22nd June 1915. Richard Meysey-Thompson attended his funeral, along with numerous other family members.”

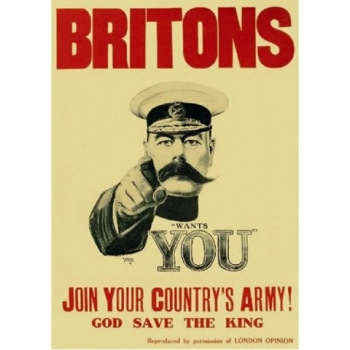

Richard’s brother, Ernest Claude Meysey-Thompson, was also a military man, having joined the Yorkshire Hussars in 1894. In 1906 he became MP for Handsworth in Staffordshire (his father’s old constituency). For part of WW1, he commanded a brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, a unit containing his son. When the war began, he played an important role in finding new recruits under the Kitchener scheme, having been asked personally by Kitchener to do so. Recruits were urgently needed, as England at that time was felt to have a very small army and quite inadequate to their then requirements. This was the campaign promoted by Kitchener’s famous Your Country Needs You poster.

Richard’s brother, Ernest Claude Meysey-Thompson, was also a military man, having joined the Yorkshire Hussars in 1894. In 1906 he became MP for Handsworth in Staffordshire (his father’s old constituency). For part of WW1, he commanded a brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, a unit containing his son. When the war began, he played an important role in finding new recruits under the Kitchener scheme, having been asked personally by Kitchener to do so. Recruits were urgently needed, as England at that time was felt to have a very small army and quite inadequate to their then requirements. This was the campaign promoted by Kitchener’s famous Your Country Needs You poster.

Ernest put out the call urging “Country gentlemen and ladies can do real good work if they personally approach men of all classes, whether domestic servants, labourers, shop assistants or those employed in farms and in small towns and ask them to come forward and enlist at once, by asking farmers to let their labourers enlist as soon as the harvest is gathered in… Farmers and other employers of labour can very greatly assist by inducing every eligible man they can spare to enlist immediately…taking them to the recruiting station in motor cars or otherwise and facilitating their enlistment by promising them that so far as is possible they will reinstate all who enlist now in their old positions when the war is over.” Richard supported his brother in this recruitment, attending recruitment meetings in York. By 1915, Ernest was saying that “he had been impressed with the patriotism of all classes. A great deal was owing to landed gentlemen, employers and the men themselves”.

The Kitchener (and similar “Derby” campaigns) had been successful in encouraging over a million men to voluntarily enlist by December 1914. However, this was not enough to keep pace with the casualties and so enforced conscription was brought in. In 1916 the the Military Service Act was brought in by the then Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. This imposed compulsory active service on all single men aged between 18 and 41, but exempted the medically unfit, married, and those of reserved occupations – usually industrial, but also clergymen and teachers. Conscientious objectors (men who objected to fighting on moral grounds) were also exempted, and were in most cases given civilian jobs or non-fighting roles at the front. These could be just as dangerous as the fighting roles – often involving being stretcher-bearers. Men who could not satisfactorily demonstrate a conscientious objection, and who persisted in their refusal to serve (‘absolutists’), suffered financial penalties, with many men also sent to prison.During the parliamentary debates, responding to those who wanted amendments to the Bill, Ernest said that he had had the privilege of being at the front, and thought it his duty to make an appeal to those who wanted amendments to the Bill to reconsider their position. He himself had lost those who were nearest and dearest. He appealed to the House to cast all argument aside and realise the necessities of the situation, to think of our Allies and how unity would cheer them and to show the greatest measure of patriotism. At the same time, York’s MP – Arnold Rowntree – was a Quaker and had been prominent in opposition to the Bill.

A second Act passed in May 1916 extended conscription to married men and the government also gained the right to re-examine men previously declared medically unfit for service. A third modification was made that year – men who had left military service due to wounds or ill-health were to be re-examined to determine whether they were fit to resume service; and a revised list of reserved occupations was published – removing the exemptions for many agricultural occupations. A fourth version of the Act was passed in January 1918, enabling the government to quash all exemptions from military service on occupational grounds (at its own discretion). Three months later, in April 1918 – at the height of the great German Spring offensive on the Western Front – a fifth version of the Act was published, extending the age eligibility so that men aged from 17 to 51 could be called up. In addition the Act was to be applied to men in Ireland, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man (although the policy was never actually implemented in Ireland).

Following the introduction of the Act, men or employers who objected to a call-up could apply to a local Military Service Tribunal. These bodies could grant exemption from service, usually conditional or temporary. There was right of appeal to a County Appeal Tribunal. The number of Quaker families living in York meant there would inevitably be a number of applications to the York tribunal. It seems from the minutes of the meetings that some members of the tribunal committee did not think kindly of conscientious objectors, and the local press supported these attitudes. In March 1916, Richard is quoted in the York Herald as suggesting that conscientious objectors should be “dressed in red and distributed along the front in the firing line…their task to be the digging of graves for the heroes who have fallen….Verdun would be an excellent place at which to commence.” (Verdun being one of the largest battles of the First World War, fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front between the German and French armies.)

The following year however, Richard (now 69 years of age) found himself before the York Tribunal, as enquiries were raised about the services of his cowman, Walter Porter. The 1911 Census shows that at Nunthorpe Court, the Meysey-Thompsons employed eight live-in staff – variously, a cook, four maids, two grooms and an elderly cowman called William Brown. There may also have been other employees, who did not live at Nunthorpe Court. At this time, the estate ran to over 33 acres and undoubtedly took a great deal of management.

The following year however, Richard (now 69 years of age) found himself before the York Tribunal, as enquiries were raised about the services of his cowman, Walter Porter. The 1911 Census shows that at Nunthorpe Court, the Meysey-Thompsons employed eight live-in staff – variously, a cook, four maids, two grooms and an elderly cowman called William Brown. There may also have been other employees, who did not live at Nunthorpe Court. At this time, the estate ran to over 33 acres and undoubtedly took a great deal of management.

The 1915 electoral rolls show the addition of a Walter Porter, whose residence and occupation are given as “Dwellinghouse, service”. In 1917, questions were being asked about why despite the war, Mr Porter had been allowed to continue to work as a cowman. The tribunal ordered Mr Porter to report for military service and heard evidence from Lieut Col R A Bottomley – the recruiting officer for York – who wrote to the tribunal intimating that Porter was being called up and indeed had reported for duty. However Richard appealed to the Board of Agriculture, who subsequently gave Porter a conditional exemption from service, so long as he remained a cowman. This was despite the amendments to the Military Service Act , which had removed the exemptions for various agricultural labourers. The case went back to tribunal, which came to the conclusion that Mr Porter was not actually engaged in agricultural work but was merely supplying necessaries to the family. It has been suggested that the view of the tribunal was that the household had nine cows, but that only three of them were in milk, and that all the milk this trio produced was only used in the household. Not only that, but the family had no arable land whatsoever and so Meysey-Thompson’s holding should not have been classified as agricultural, and as such, the Board of Agriculture should not have been able to exempt Porter. Commentators have suggested that despite his views on conscientious objectors, Richard’s patriotism was of the nimby variety, and that he had been allowed the services of a soldier he had tried to keep out of the army, whose job was simply to ‘cultivate’ their garden. The tribunal again assessed Mr Porter as fit for service and withdrew his exemption and he was ordered to take up work of national importance.

Lieut Col Bottomley’s evidence this time was that since he had last written to the tribunal, he had been informed that Mr Porter had obtained a further extension and also that another soldier had been obtained by the Meysey-Thompsons. He said the man would be there indefinitely at the command of the officer commanding the Agricultural Company at York. The Sheriff of the tribunal (Mr C W Shipley) said that if the Army had sufficient men to lend Col Meysey-Thompson men to supply his household with necessaries, it must not be in need of men and the tribunal had no right to send men into the Army. The tribunal had tried to deal with people, irrespective of social position, yet here they found the Colonel could do what he liked, while other men had to close down their businesses. Lt.Col Bottomley said his own opinion was that when the Colonel had got his hay in, the men ought to be returned. This dispute caused a strike by the local tribunal, who, frustrated by their decisions being overturned by other Boards, announced they would suspend all sittings until the War Office ruled on the matter. Two months later, the case was re-heard by the tribunal, who after further discussion, came to the same conclusions but this time directed the Clerk to write to the officer commanding the Agricultural Company, setting forth the views of the tribunal, presumably to ensure that no further extensions were granted.

This case was widely reported in the local press and must have caused bad feeling at a time when many families, including those surrounding Nunthorpe Court, had lost loved ones in the war. One also wonders what the rest of the Meysey-Thompson family must have thought, given their prominent voices in encouraging men to join up. However, one also must have some sympathy for Richard. He had previously fought for king and country, had lost family members to the War and was 69 years of age and in ill health. He had been brought up at a time when the Empire was at its peak. Aristocratic families with estates needed, indeed expected to have assistance, in running their estates. The old expectations that land owners were responsible for their land and for the people who worked on it, would no doubt have been felt keenly by him. He could not have maintained the land on his own. It comes as no surprise that five years after the war ended, Richard had sold the estate, partly to the Council to found Nunthorpe Grammar (now Millthorpe School) and partly to create the housing on Nunthorpe Grove and Crescent. The position Richard found himself in illustrates the dilemma many landed families faced at the time.