Mother, shall we have to kill Fräulein?

‘Mother, shall we have to kill Fräulein?’ From Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol 147, 2 Sept 1914

‘Mother, shall we have to kill Fräulein?’ From Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol 147, 2 Sept 1914

These xenophobic times remind us of past anxieties. A popular Punch cartoon in 1914 reflected growing concerns about Germans living in Britain at the time. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it had been common for German women to take up posts as governesses in British upper class households. But this gave rise to problems once the war started, as the prevailing anti-German sentiment meant that they were seen as potential spies. It was particularly worrying if they were working in a military household. There were even rumours of German ‘secret order books’, which described how the German authorities might place governesses in positions where they could learn about military plans.

‘Germans’ is a loose term for a number of reasons, as Germany was a new entity in the 19th century. Some ’Germans’ had come to Britain many years previously and felt assimiliated even if they were not naturalised. There was also prejudice against people for having a German name, even if they were British or naturalised.

As early as the end of August 1914, the Yorkshire Evening Post was confident that nearly all the Germans in the country had been located and registered, in ‘the hunt for spies’. They reported that ‘Secret Service men’ were watching suspected Germans and visiting houses, especially those with a German governess. One press report noted a story from a ‘northern suburb’, when police had called, asking about a German girl living there, the people said she had been there so long they had almost forgotten she was German. Horrifyingly when the police searched her room they apparently found two bombs. However by the end of the war these sort of stories were being described as mere rumours, with no foundation in truth.

Local evidence

On August 5, 1914, the Aliens Restriction Act came into force, preventing Germans who were resident in Britain from travelling more than five miles from their homes, or from living in ‘prohibited areas’. To house those who were interned, a temporary detention centre was set up near Clifford’s Tower at the Castle Prison, with a tented encampment. Later on a larger camp was built in Leeman Road, as York became a detention centre for people from across the country. Eventually internees were held in a camp on the Isle of Man. These policies were influenced by public opinion as well as government action. Even residents who were naturalised were not safe, as the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act of August 1918 gave the Home Secretary sweeping new powers to repeal the naturalisation certificates of former alien subjects.

A search through the 1911 census for York has actually revealed just a small number of German‑born residents in that year, only 62, of whom merely half a dozen were living in our neighbourhood. Furthermore there were no Turks, Austrians, Hungarians, Poles or Bulgarians in our area who might have been interned.

Louisa Gebhard was a 49 year old German, living at 21 Balmoral Terrace in South Bank with her York-born family. She was a naturalised widow, whose late husband, Charles (Carl) Gebhard, had been a German pork butcher, previously in Holgate. German pork butchers in Britain were heavily victimised during the war, especially after the sinking of the Lusitania, and so Louisa escaped this fate. However she did not survive the war, she died in 1915.

Carl Otto Muller was a 73 year old German optician, living with his York-born family at 53 Bishopthorpe Road. He had previously been living at 47 Fairfax St in 1871, when he was described as an instrument maker (almost certainly using his specialist skills working at T. Cooke & Sons in Bishophill). Carl died in 1913.

Julie Elizabeth Press was 26, living at 40 Fairfax St, the naturalised German wife of a York‑born NER wagon builder, with two English children.

Robert Werner Oberhoffer (56) was a notable German composer, organist and music teacher, living at 9 The Crescent, off Blossom St in 1911, with his German wife Marie Elizabeth, their York-born daughters and his German nephew, Gerhard Oberhoffer (23). Robert was closely associated with St Wilfred’s Church in York. His son, George Oberhoffer, born in 1885, was by 1913 a music master at Uppingham School. As the war developed, in January 1915 George joined the 18th Battalion Royal Fusiliers (1st Public Schools), and was sent to the Front in November 1915. It is intriguing that a man with such a distinctive German name, albeit York-born, was accepted into the British Army. He only survived a few months, suffering a shot to the head in February 1916, and was buried at Bethune in France. His father Robert sadly died a few months later, in July 1916, aged 61.

Lastly, Magdelena Heidrich was a twenty-nine year old German governess, living in 1911 with Osbert and Constance Lumley and their family, and their nine other servants at Townshend House on the east side of The Mount. Osbert was a son of the 9th Earl of Scarborough, and a Brigadier‑General in the 11th Hussars. In 1910 he had been appointed Colonel-in-Charge of Cavalry Records (Hussars).

Apart from Gerhard Oberhoffer, none of the German-born residents in our area would have been interned in the war, as they were either female or too old. If Gerhard were still around in 1914 then he would have been taken away and interned. But did the Gebhards, the Mullers and the Oberhoffers, with their German names, suffer from anti-German prejudice during the war?

The German governess and the writer

The German governess, Magdelena Heidrich, living with the Brigadier‑General and his family at Townshend House on the Mount, is intriguing to us for a particular reason.

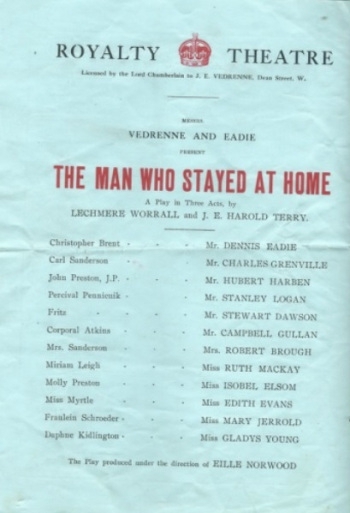

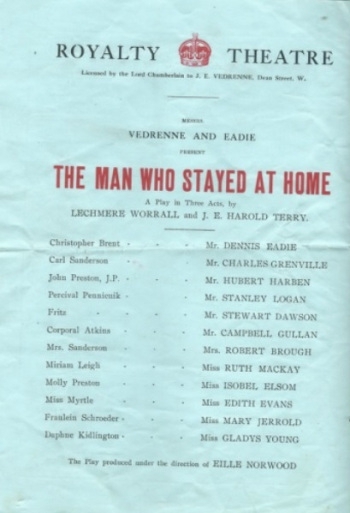

Writing on the British Library European Studies blog about the issue of German governesses, Susan Reed, Lead Curator Germanic Studies, draws attention to a popular play, The Man Who Stayed at Home. Written by JG Harold Terry and Lechmere Worrall in 1914, it was quite successful at the time, and was filmed twice and adapted as a novel. It features a group of people in a seaside hotel, including a German governess Fräulein Schroeder. She turns out to be a spy, along with some of the other characters.

A little investigation of JG Harold Terry reveals an interesting surprise. Born in 1885, he was a member of the illustrious Terry family of York, a brother of Noel Terry, who was responsible for the confectionery firm Terry’s of York from 1923 onwards. In 1911 both Joseph and Noel were living at Trentholme, on the Mount. This house was a few doors from Townshend House, where the German governess Magdelena Heinrich was living in 1911. We might therefore suppose that Joseph drew upon his knowledge of Magdelena in writing the play. He may have been inspired by the idea that Osbert Lumley was a senior military figure and therefore potentially at risk from spying by a German national.

Joseph joined the London Regiment (Artists Rifles) in September 1914 but seems to have been considered unfit for further military service and was discharged after three months. He was by now living in London. He died on the Isle of Wight in 1939 aged 53.

Note

‘Mother, shall we have to kill Fräulein?’ From Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol 147, 2 Sept 1914

‘Mother, shall we have to kill Fräulein?’ From Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol 147, 2 Sept 1914