26th October 2018

What was it like to be poor in 19th century York?

Dick Hunter reports on progress with our Poor Law project

Our new history group project is using the recently catalogued Poor Law records in Explore York, to help us to understand how poverty was experienced in 19th century York – and to give a voice to the poor themselves.

The focus is on one parish – St Mary’s Bishophill Junior, an area of central York both inside and outside the city walls. Our volunteer researchers are looking at records of three periods: 1839-43, 1859-63, and 1879-83. The aim is to identify a sample of individuals whose lives we can attempt to track, collecting their life stories to show their contact with the relief system.

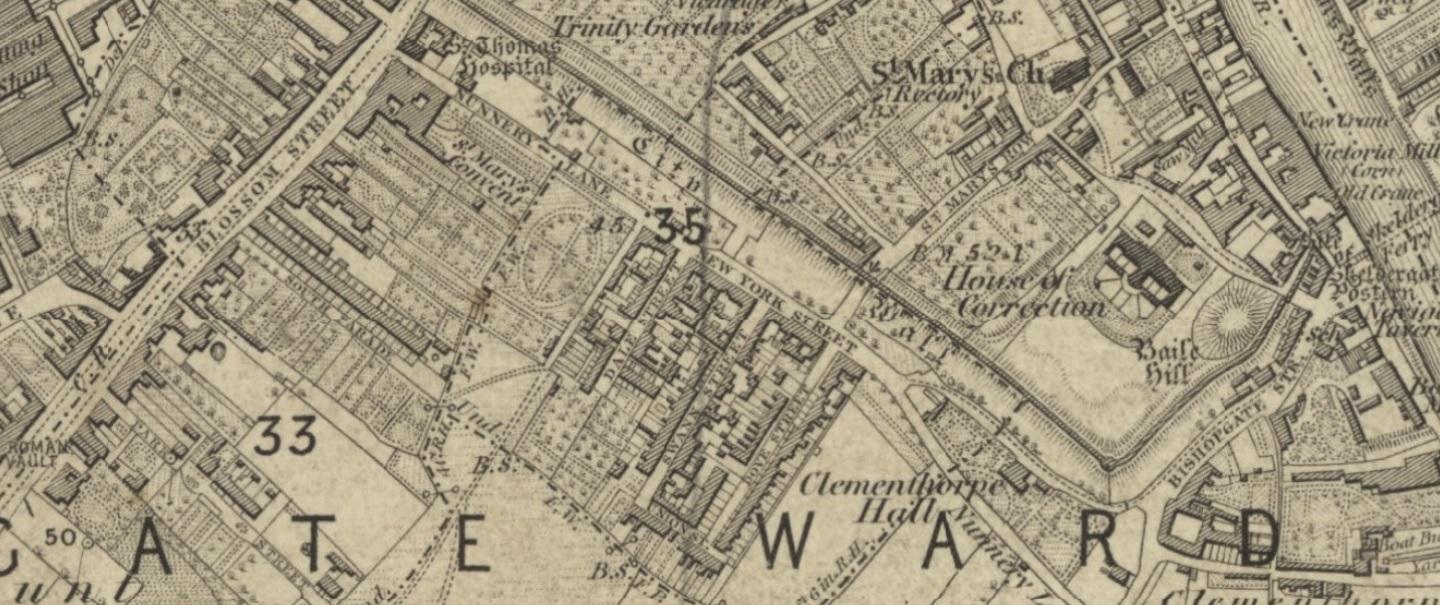

Extract from map of York showing the parish of St Mary's Bishophill Junior, OS six inch map Yorkshire 174 surveyed 1846-51; pub. 1853. See https://maps.nls.uk/view/

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

The relevant streets at the time were Nunnery Lane, Dale St, Swann St, Dove St, Union St, St Mary's Row (Victor St), Priory St and Cromwell Rd.

To claim relief a person had to have the right of settlement in a parish administered by the York Poor Law Union. This might be confirmed by various means, such as birth, marriage, residence in an area for a particular time, employment, or through various property qualifications. For our project we’re interested in anyone applying for relief for whom St Mary’s Bishophill Junior was responsible.

Emma Miller Stephenson (1804-1879): a case study researched by Pauline Alden

Born Emma Miller in Filey in 1804, Emma married Thomas Stephenson in Whitby in 1831. In 1841 they lived in Easby, near Stokesley. Thomas Stephenson died in 1843 and by 1851 Emma was living in Park Street, York, employed as a servant in a large household.

Emma married Christopher Doughty, a carpenter, in 1852. He had a daughter Anne, born in York in 1822, from a previous marriage. In 1861 they lived in Dale Street. Unfortunately, Emma lost her second husband in 1867.

Aged 67 in 1871 Emma, now a seamstress, was living with her niece at 14 Dale Street. In December 1873 she made the first of four applications for assistance from York Poor Law Union, citing chronic bronchitis. She was awarded a shilling weekly, plus three shillings for rent. She continued to suffer from bronchitis and in March 1875 was recorded by the Relieving Officer as not able-bodied. She received three shillings, and brandy valued at a shilling.

In March 1876, now a widow with continued bronchitis, she got medical relief valued at two shillings and six pence, and two shillings and ninepence outdoor relief. In September 1877 she received three pounds of mutton worth a shilling and eight pence.

Emma Doughty died of bronchitis on the 20th December 1879 in Swann Street. She was buried by William Dimmey, undertakers of Victoria Steet, in a public grave with no headstone.

It was not only people living in this area that used local parish resources. For example, in 1837 Joseph Spink (40) was an unemployed whitesmith living in the Shambles. A widower with four children – George, Joseph, Mary Ann and Henry – he was awarded eight shillings relief. The 1851 census records Henry as fifteen, a servant, living in Bishophill with his grandparents John and Mary Tempest.

The aim of our project is to place an individual’s experience in context: how did the parish deal with its poor, and how much did it spend? Was a child on relief more likely to grow up to be an adult on relief? How did a large family – or bereavement – affect reliance on relief?

Explore York has one of the best collections of post-1834 out-relief records in the country. Out-relief allowed people to receive relief in their own homes, rather than enter the workhouse.

Application and Report Books (PLU/3/1), catalogued by ecclesiastical parish, offer a wealth of data for research: name of claimant plus address, age, marital status, occupation (e.g. charwoman, soldier’s wife, shoemaker) and any disability. They also give the reason for seeking relief, whether relief is temporary or permanent, and details of relief from other sources such as charities. Where relief is in cash, the value and length of period of relief is noted. If in kind – for example, flour, tea or candles – quantities and period are recorded.

We’re also looking at Outdoor Relief Lists (PLU/3/2). These name paupers, and total relief received weekly, plus amounts received per quarter and half year. They also include statistical columns, for example by gender, marital status, children and vagrants.

Volunteers will be looking at the role of the Relieving Officer, using a 19th century Manual for Relieving Officers (PLU11/5/4/9). Other useful sources include Board of Guardian minute books, census data, birth, marriage and death registers, and Ordnance Survey maps for 1836, 1852 and 1889.

Archivist Julie-Ann Vickers and Kate Gibson from the University of Sheffield have been training our project volunteers, who have also been using a series of short guides to Poor Law records.

For further details of our project contact enquiries@clementshall.org.uk